mi·cro·plas·tic (mīkrō-plăs′tĭk)

n.

A tiny plastic piece, fragment, or fiber, especially one that measures less than 5 millimeters in length or diameter.

The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition copyright ©2022 by HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved.

F.D.A.

Microplastics and nanoplastics may be present in food, primarily from environmental contamination where foods are grown or raised. There is not sufficient scientific evidence to show that microplastics and nanoplastics from plastic food packaging migrate into foods and beverages. People may be exposed to microplastics and nanoplastics through the air, food, and absorption through the skin from the use of personal care products.

Microplastics and nanoplastics are found in a wide variety of sizes, shapes, and colors, as well as varying polymer types, states of degradation, and presence of chemical additives included in plastics during the manufacturing process. Microplastics are very small pieces of plastic that are typically considered less than five millimeters in size in at least one dimension. Microplastics can be manufactured to be that size, such as resin pellets used for plastic production, or degraded to that size from larger plastics discarded into the environment. Nanoplastics are even smaller, typically considered to be less than one µm, or micron, in size. For reference, the diameter of a human hair is about 70 microns.

www.fda.gov

www.fda.gov

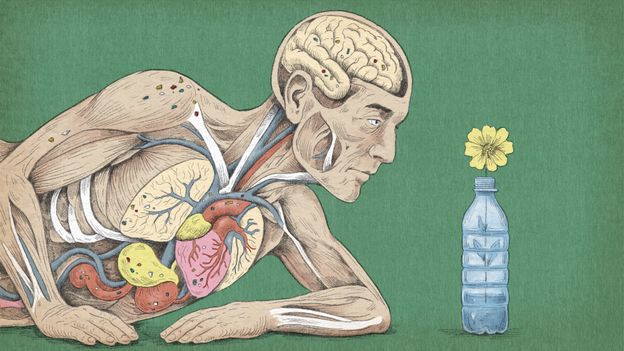

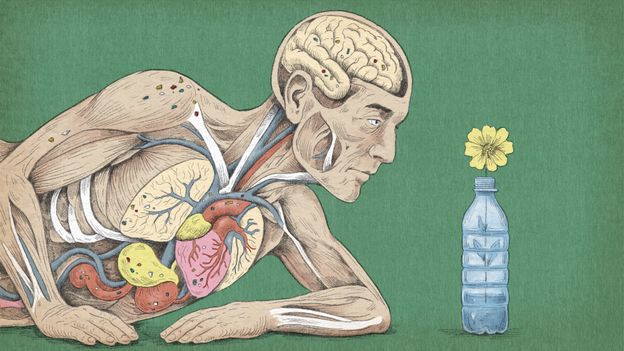

According to one famous estimate, we might consume up to 52,000 microplastics per year, and while that precise figure has been subsequently challenged, it's clear that they are entering the human body in significant quantities. Whether ingested through our food, the liquids we drink, or absorbed from the air we breathe, microplastics have become ubiquitous. They have been found in bodily fluids from saliva and blood to sputum and breast milk, along with an array of organs including the liver, kidneys, spleen, brain and even the insides of our bones. This steady convergence of evidence has all pointed to one question – what exactly is all this plastic doing to our health?

Today it's thought that around the world, humans are ingesting and inhaling more microplastics than at any time in recorded history. In a study published in 2024, scientists found that consumption of the particles has increased sixfold since 1990, particularly in various global hotspots including the US, China, parts of the Middle East, North Africa and Scandinavia.

But finding out how they are affecting our health has proved tricky. One way to find out is what's known within medical circles as a "human challenge trial". Usually carried out in the realm of infectious diseases, it involves participants agreeing to be deliberately infected with a pathogen in order to help scientists better understand its effects on the human body.

Then in February 2025, another group of scientists identified microplastics in the brains of human cadavers. Most notably, those who had been diagnosed with dementia prior to their death had up to 10 times as much plastic in their brains compared to those without the condition. "We were shocked," says Matthew Campen, a University of New Mexico toxicology professor who led this study.

When it comes to the brain, Campen's current belief is that tiny plastic particles circulating in the bloodstream might be hijacking the brain's high metabolism and hitching a ride into our central nervous system on the back of the fats known as lipids which it requires for energy.

"We also think that the high lipid content of the brain, especially in white matter, makes for an ideal environment for these plastics," says Campen. "The brain also has a notoriously slow clearance mechanism, and in dementia, the blood brain barrier [which is designed to stop foreign objects accessing the brain] is impaired, further aiding uptake of plastics."

www.bbc.com

www.bbc.com

Currently there doesn't seem to be much hope in expelling microplastics from living human bodies, for example the way neurotoxic heavy metals can be reduced by chelation.

Any chance of reducing our intake?

Might this environmental hazard drive us back to using glass bottles?

n.

A tiny plastic piece, fragment, or fiber, especially one that measures less than 5 millimeters in length or diameter.

The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition copyright ©2022 by HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved.

F.D.A.

Microplastics and nanoplastics may be present in food, primarily from environmental contamination where foods are grown or raised. There is not sufficient scientific evidence to show that microplastics and nanoplastics from plastic food packaging migrate into foods and beverages. People may be exposed to microplastics and nanoplastics through the air, food, and absorption through the skin from the use of personal care products.

Microplastics and nanoplastics are found in a wide variety of sizes, shapes, and colors, as well as varying polymer types, states of degradation, and presence of chemical additives included in plastics during the manufacturing process. Microplastics are very small pieces of plastic that are typically considered less than five millimeters in size in at least one dimension. Microplastics can be manufactured to be that size, such as resin pellets used for plastic production, or degraded to that size from larger plastics discarded into the environment. Nanoplastics are even smaller, typically considered to be less than one µm, or micron, in size. For reference, the diameter of a human hair is about 70 microns.

Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Foods

Microplastics and nanoplastics may be present in food, primarily from environmental contamination where foods are grown or raised.

According to one famous estimate, we might consume up to 52,000 microplastics per year, and while that precise figure has been subsequently challenged, it's clear that they are entering the human body in significant quantities. Whether ingested through our food, the liquids we drink, or absorbed from the air we breathe, microplastics have become ubiquitous. They have been found in bodily fluids from saliva and blood to sputum and breast milk, along with an array of organs including the liver, kidneys, spleen, brain and even the insides of our bones. This steady convergence of evidence has all pointed to one question – what exactly is all this plastic doing to our health?

Today it's thought that around the world, humans are ingesting and inhaling more microplastics than at any time in recorded history. In a study published in 2024, scientists found that consumption of the particles has increased sixfold since 1990, particularly in various global hotspots including the US, China, parts of the Middle East, North Africa and Scandinavia.

But finding out how they are affecting our health has proved tricky. One way to find out is what's known within medical circles as a "human challenge trial". Usually carried out in the realm of infectious diseases, it involves participants agreeing to be deliberately infected with a pathogen in order to help scientists better understand its effects on the human body.

Then in February 2025, another group of scientists identified microplastics in the brains of human cadavers. Most notably, those who had been diagnosed with dementia prior to their death had up to 10 times as much plastic in their brains compared to those without the condition. "We were shocked," says Matthew Campen, a University of New Mexico toxicology professor who led this study.

When it comes to the brain, Campen's current belief is that tiny plastic particles circulating in the bloodstream might be hijacking the brain's high metabolism and hitching a ride into our central nervous system on the back of the fats known as lipids which it requires for energy.

"We also think that the high lipid content of the brain, especially in white matter, makes for an ideal environment for these plastics," says Campen. "The brain also has a notoriously slow clearance mechanism, and in dementia, the blood brain barrier [which is designed to stop foreign objects accessing the brain] is impaired, further aiding uptake of plastics."

How do the microplastics in our bodies affect our health?

Microplastics have even been found inside our bones – but what impact are they having on our health? Here's everything we know about what they're doing to our bodies.

Currently there doesn't seem to be much hope in expelling microplastics from living human bodies, for example the way neurotoxic heavy metals can be reduced by chelation.

Any chance of reducing our intake?

Might this environmental hazard drive us back to using glass bottles?